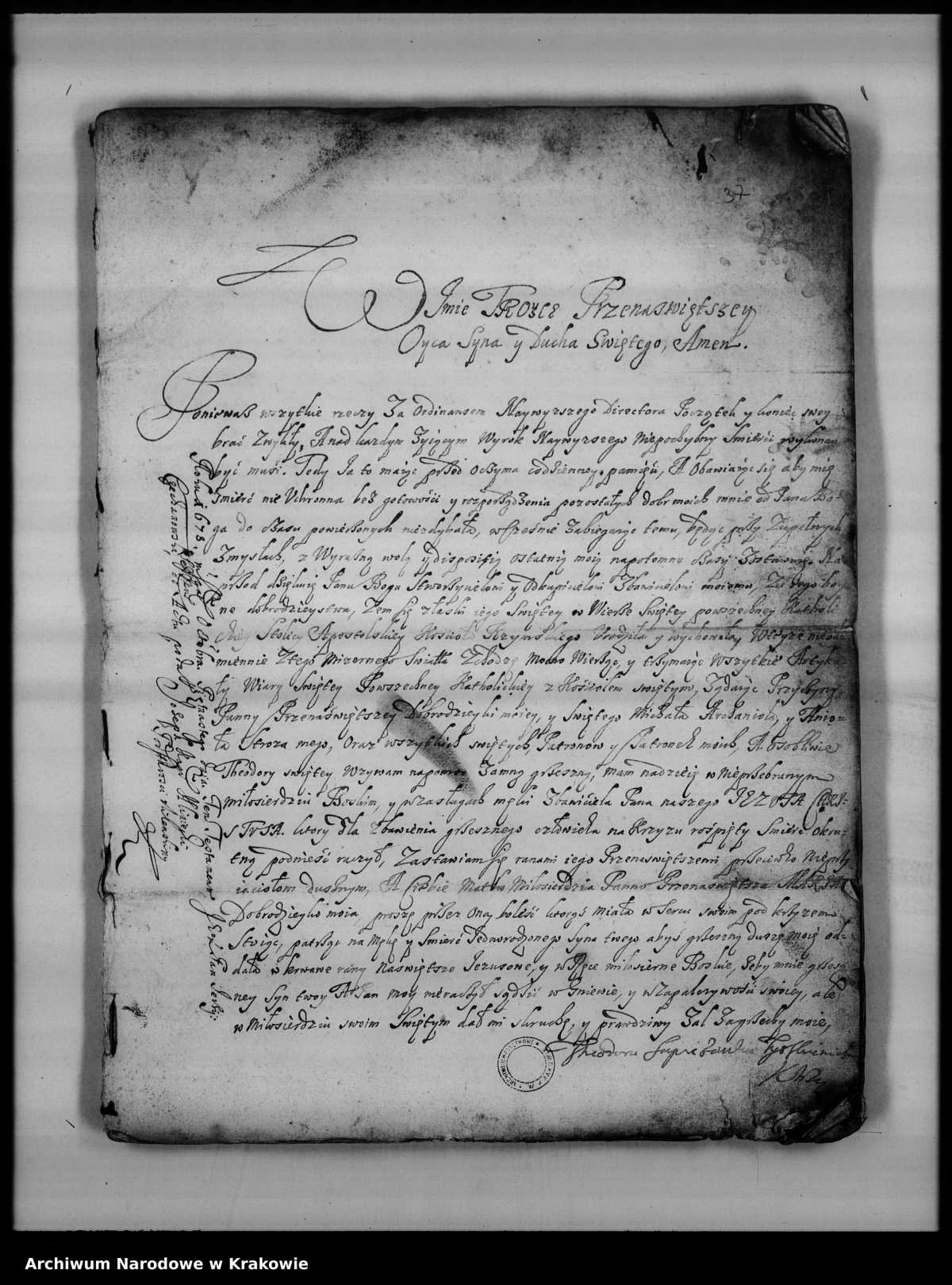

The wills are also a testimony to the religiosity of peasants. Due to their rich content, they are considered by linguists as evidence of dialect and regional vocabulary. These documents were used in the settlement of property disputes as evidence that indicated the intentions of individuals as recorded in the records made.

In the publication Polish Peasants over the Centuries. The state of research and research perspectives, one can read Janusz Losowski's extensive article on the subject. The author undertook the study of the thread related to wills in more detail. He described specific cases of wills left by people writing last wills in the 17th and 18th centuries in the Przemysl and Sanok lands or in the Szczyrzycki and Biecki districts, as well as in villages near Krakow, such as Krowodrza and Nowa Wieś.

Of primary importance in the question of rural wills are village court records, where statements of the last will were entered. Such files have been preserved to a small extent and unevenly, if their territorial origin is taken into account. Interest in wills as the most valuable component of village court records is therefore justified. This is because this documentation is a consequence of research related to the daily life of peasants in the Old Polish period and their legal position, property status, family situation or religiosity.

One such will is the act of the last will of Stanislaw Kolodziejczyk, who in 1771 in Trzesniowa (Sanok region), having five sons, three of them - Stanislaw, Casimir and Bartholomew - distributed part of his estate. He secured his wife in a similar manner. However, it is not known why his other two descendants - Joseph and John - received nothing in the written document. There is a probability that they were minors and remained in their mother's care. The three aforementioned endowed sons appeared before the local assembly office and approved their father's estate decisions contained in the document, and pledged not to question them in the future by signing their names to it. The will was also approved by a representative of the manor and the local gathering office. After the document was entered in the collection records, the heirs received it, as it had significant evidentiary value for them.

Another act of the last will, the will of Maciej Kosek called Bartus, who lived in Osobnica in the Biecz district, is also worth mentioning. Despite the fact that he had four sons, the testator decided to exclude them from the inheritance. The reason for this was their lack of help with farm work. Wanting to prevent them from trying to undermine the property dispositions he had made, he threatened them with heavy fines to the local church, the manor house and the assembly office.

From Old Polish wills, therefore, it is possible to learn a lot of details about family conclusions in the villages at the time.

Property dispositions, in turn, mainly concerned land used by the testators (meadows, fields, pastures, or even wasteland). They also included equipment necessary for farming, craftsman's tools, household furnishings, bedding, kitchen utensils, pans, and clothing.

There were also documents that contained only dispositions of movable property, due to the poverty of the testators. An example of such a document can be found in the will of Maria Klepaczówna of Tork in the Przemyśl region, in which the testator disposed of only her clothing.

First and foremost, however, the wills concerned property dispositions regarding land used by the testators, and these were fields, meadows, pastures, or wastelands. The documents also included equipment needed for farming (plows, radles, soches, harrows), or tools of the trade, such as axes, saws and chariots. Household furnishings (tables, benches, chests) were also included in the estate distribution documents. Sometimes testators took out loans for various purposes, so they had to issue instructions on how to settle them.

Testators often disclosed to their heirs the sums lent to others so that they could collect them from the testator's debtors in the course of executing the provisions of the will they drew up.

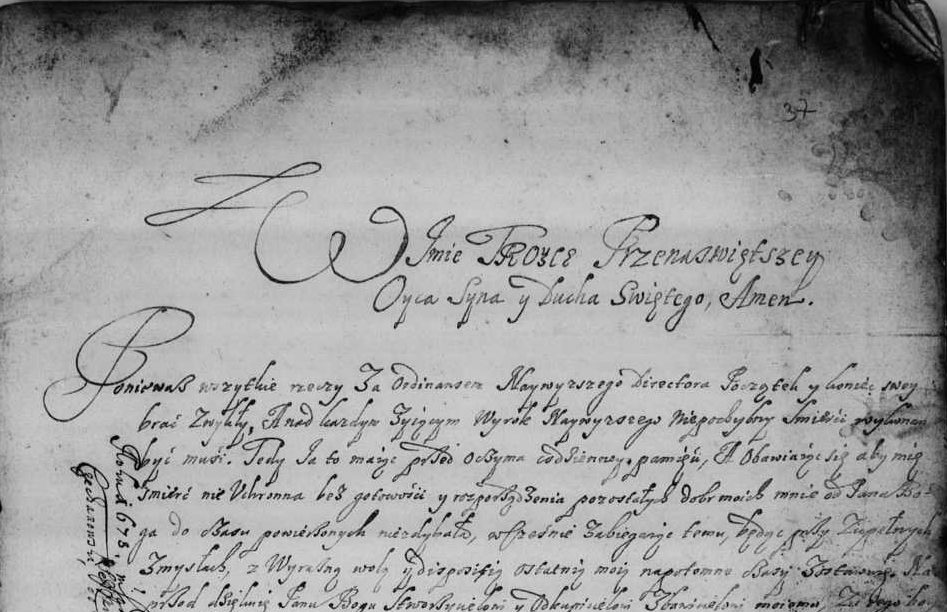

The wills of Polish peasants also contained religious content. Brief confessions of faith of testators were recorded in the documents. There were also pledges by these individuals to observe Christian values in their lives and their religious practices. Declarations about making distributions in the name of God were placed in the documents, which provided even more convincing evidence of the will-makers' giving a religious character to the secular act of distributing property among the relatives of the person writing the document.

Declarations of devotion of the soul to God were also recorded in testamentary statements. It also happened that people making a will expressed thanks to God in the document for receiving the gift of the Catholic faith and persevering in it.

You can learn more about the details of the last will deeds drawn up by the inhabitants of an Old Polish village by reading the article Functions of peasant wills in the Old Polish period in the publication Polish Peasants over the Centuries published by the NIKiDW. The state of research and research perspectives.

Read the article.

The book Polish Peasants over the Centuries. Research status and research perspectives is available in the publisher's online store.

Oprac. na podst. artykułu Janusza Łosowskiego Funkcje testamentów chłopskich w okresie staropolskim, [w:] Chłopi polscy na przestrzeni wieków. Stan badań i perspektywy badawcze, red. M. Wyżga i J. Załęczny, Narodowy Instytut Kultury i Dziedzictwa Wsi, Wydaw. Akademii Humanistycznej, Warszawa 2023, s. 27−54.

Photo: National Archives in Krakow

Elaborated. Arkadiusz Olszewski